By: Garrett Bethmann

I’ve never really written about art, at least not the visual stuff. Music has always been my muse in terms of the written word. I’m nervous on how to find the right words to express the way art might move me or explain to people what might be happening on a canvas. It’s a medium I don’t know, an impressionable target I don’t know if I can hit with my prose. I feel untrained and unqualified to speak to what I see but do not know.

In that sense, artist and musician Abe Partridge is the perfect person to talk to for my first time. Partridge is a Mobile, Alabama native who too thought music and art were for “trained people,” a skill and profession that needed years of instruction and a clear path towards creating products that might eventually find themselves prominently displayed in a gallery or the decorative section of a Walmart. Thankfully, it was a notion that didn’t last forever, though it took a stint fighting in the Iraq War in 2014 for the 40-something to finally change his perspective.

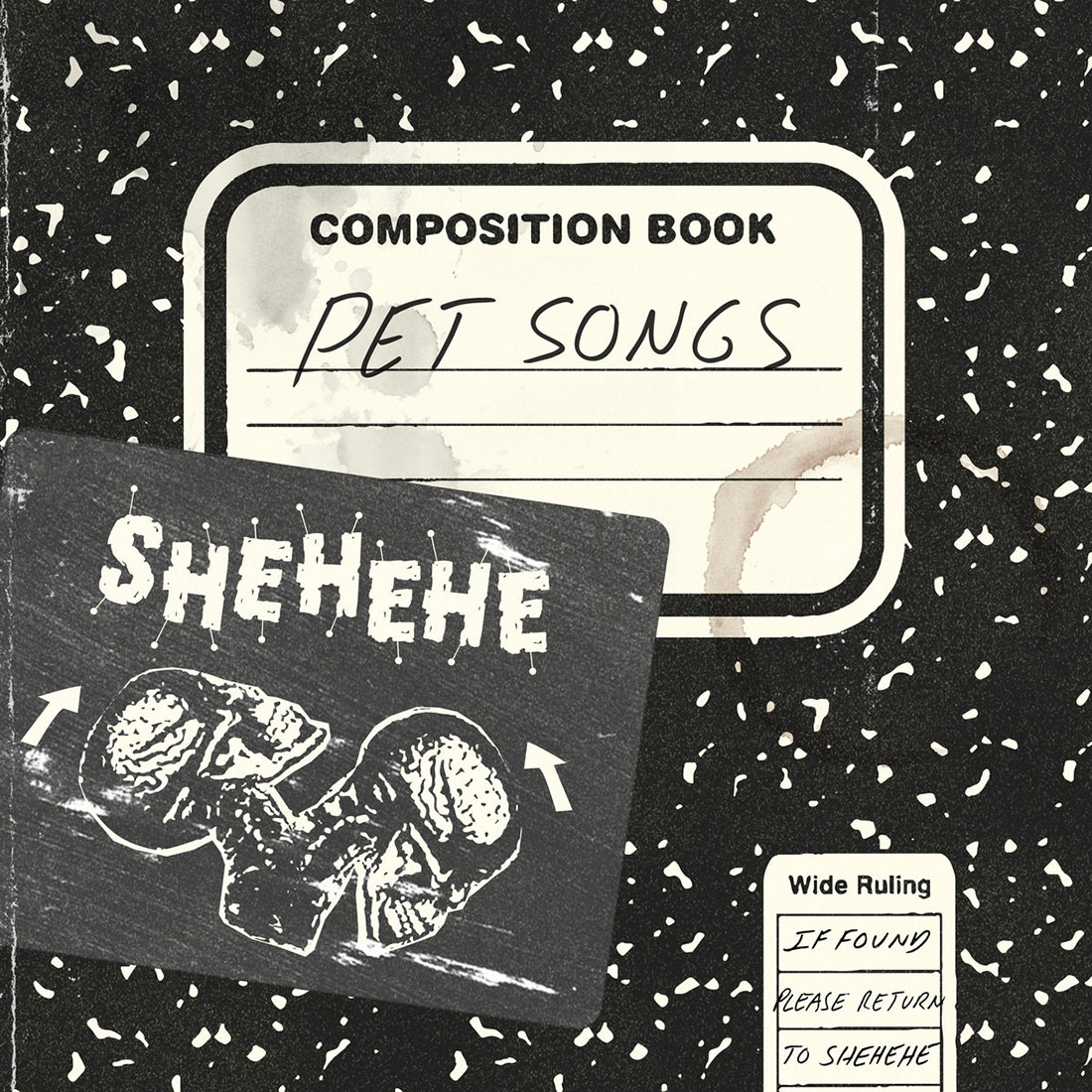

Since his return, Partridge has made a commitment to follow his musical and artistic passions as faithfully as he can, without overthinking too much about what comes out of him, which is a visceral combination of weird, true and beautiful scenes and characters. From the musical side of things, it means being an empathetic songwriter that sings with the reedy huskiness of burnt kindling, lighting the fires of inspiration inside him that speak to blue-collar love (“Our Babies Will Never Grow Up To Be Astronauts”) and small-town secrets (“The Ghosts of Mobile”) among other stories that mark his 2018 album Cotton Fields and Blood for Days. It makes sense he released a cover of Nirvana’s “Dumb” this spring, lending his sensibilities to a prickly sweet spot from a band who defined for millions of people what it was to be weird, true and beautiful.

“I’m just like every kid of my generation, Nirvana was the first real music I ever fell in love with and the first time I really ever heard music. When I ever heard Nirvana, it was the first time I really understood what was powerful about music,” said Partridge.

In terms of his visual art, The Alabama Astronaut comes from a place where you paint the quiet things inside you out loud. Glopped and smeared in tar and scrawled onto whatever canvas finds itself in front of him, Partridge delves into a surreal world of twangy, skeletal figures and confessional prose that is unvarnished and enticing, striking in its uniqueness.

He’ll paint on shoes, he’ll paint on records. He’ll paint pretty stuff like Ahmad Aubrey over a Confederate flag license plate or he’ll paint ugly stuff like the cops from Mobile who created a “homeless quilt” that went viral last winter. He’ll paint portraits for other singular artists who don’t mind stripping down to the floorboards of guttural expression, like musical-visual artist Will Johnson and Drive-by Truckers’ Patterson Hood. His vision is meant to only represent humanity and no matter the canvas, each piece is an opportunity for Partridge to create whatever crooked beauty might be living inside him that moment.

“As far back as I can remember I was always trying to create something that I thought was beautiful. I got poems in my house from when I wrote in the third grade, just trying to put words together in ways I thought was beautiful. I had no idea I’d ever be doing it in my life but it’s always been something I’ve loved to do,” said Partridge.

Abe Partridge is some vernacular shit, painting and speaking in the tongue of someone untrained in process or technique but artfully capable of conveying their emotions in the most natural way possible. But don’t bother overthinking his eccentricities, just be content feeling the weird, truthful beauty of it. You are qualified to feel whatever you may.

Read below for an interview with Abe Partridge. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why does “making something beautiful” appeal to you?

I had kind of a troubled childhood and it was probably my attempt to cope with it. I’ve always liked weird stuff. If I went to go get a movie as a kid, I went to the weird, odd sections, cause the conventional stuff was so boring. South Alabama is not known for being a cultural Mecca, so it was easy for me to create my own thing than to try and find stuff that I liked.

Growing up down here, I just figured being an artist was like being a doctor, you went to school for it. It was an understanding I had and it was years later until my views changed. I just figured my stuff wasn’t no good and nobody would appreciate it. There’s definitely no education there, it’s just whatever comes out.

What flipped that switch for you?

I was in a war and when I was over there in 2013 and 2014, I realized I had spent my entire adult life bringing negativity and violence into the world. It was negativity in the kind of preaching I had done and violence is the work of the military. I turned 35 in the desert that year and it was kind of a hard thing to swallow. I had been writing songs since I had left the ministry, I’d been painting about the same time. I said when I got home I was going to start singing my songs and that’s what I did. I played one songwriter’s contest and it changed my life. Now it’s what I do.

Between art and music, are there different end goals? What can each do for you that the other can’t?

I never really think about it that deeply. I got one room where I just have papers and guitars and banjos and I got my garage that’s set up with a big table and lots of paint and tar. I just walk into whichever room I want to (laughs). I just go out there and do it. To me it’s more important to just follow your heart and not over think it too much. If I start thinking about what I want to say in a painting or what I want to say in a song, I get in the way of myself. You just gotta let it come out and sometimes the song will write itself or the painting will paint itself if you let it come out.

Whether you finish a visual piece or musical piece, do you feel a different kind of satisfaction?

It is different. If I write a song and I really feel that it’ll be something people will appreciate, it seems songs give back; the return on investment is way better. You do a painting and somebody likes it or buys it or it goes on Instagram. You make that song and I’ll sing that song for years from now. The songs that got a little something special in them that makes them be something you can play for a long time seems to get me really excited because they are so hard to come by.

You did a piece on two cops in Alabama who were photographed with a “homeless quilt,” of which I quite enjoyed the dunce caps on them. Why did you feel compelled to reflect on that specific instance with that specific piece of art?

I was born and raised in Mobile and that’s where I currently reside. This was some really tasteless thing that happened with some cops around Christmas time. They say confiscate but that’s what they say when the government steals your stuff and they confiscated these signs homeless people had asking for help and they taped them all together and made a big social media post. It became international news and it was really a black eye for our community.

I saw the image and probably everybody that has a conscience was repulsed by it. I figured I’d paint it to kind of give a response. I’m by no means popular, even in Mobile, but there’s a lot of people who pay attention to my stuff on Mobile. When I put it out there it just kind of went viral so I just decided to raise money. I think it was $4,000, we ended up giving it to a local homeless shelter for women here in town. It got me a whole bunch of press, got a whole bunch of money for the homeless, I kind of hope they do something like that again (laughs).

Do you subscribe to the belief the artist is meant to comment on the world in which they live? Is there a societal duty or responsibility of artists to do anything?

I think that goes back into the category of overthinking things. I’ll paint whatever my heart needs to paint and I ain’t scared to say anything that my heart needs to say. If anybody says I can’t say what I feel, well, it’s not their heart in my chest, it’s mine. I just have to be true to myself. I definitely love Bob Dylan and all those kinds of guys that speak to the world around them, I think it’s beautiful when they do. I would never discourage anyone from doing that and I wouldn’t want to get in the way of anything my heart needed to say, because I felt like I did or didn’t have an obligation to say something.

Wouldn’t that be kind of pretentious, to feel like I have a duty to speak to the world around me? But that one jumped out the screen for me. You see this terrible picture of these two fat cops with a bunch of signs they stole. It struck me as something that should be universally criticized. But instead with our infatuation with badges and uniforms and pieces of papers with words on them, we think its ok to treat them less than respectfully.

I understand you’ve been working on a new album. What would you care to share about the album at this point?

I recorded a number of songs after my first gig. I got one gig and met a guy, Shawn Byrne, who is a great producer, songwriter, musician, who has become my friend. He invited me to Nashville and I stayed at his house and we recorded this record, right after my first gig. I printed 1,000 CDs and sold them all and I never put it out on a digital platform. I got a number of songs from there and I recorded about 12 new tracks. I release the record then don’t play anything from the record live, I’ve already written some new songs I like better (laughs). So most of these songs I’ve played before. It’ll be in my opinion my best work yet.